Seven years ago, Pippa Biddle wrote a blog post about volunteering abroad. She recounted her struggles speaking Spanish to children living with HIV in the Dominican Republic and how local people in Tanzania would spend all night redoing the construction work she and her classmates had done poorly.

“Taking part in international aid where you aren’t particularly helpful is not benign,” Biddle wrote. “It’s detrimental.”

The blog post, which had more than 2m hits, resonated with a movement of people who felt similarly uneasy about the growing number of unqualified volunteers in orphanages, schools and hospitals around the world.

Biddle was 21 at the time and knew little about the subject beyond her own experiences. “I thought I invented the term voluntourism,” she says. “I didn’t know it was a term people used.” The response encouraged Biddle to research volunteer tourism and the ways it has and continues to harm the people it aims to serve, and to write her book, Ours to Explore: Privilege, Power, and the Paradox of Voluntourism.

A growing industry before the pandemic, the global annual figure for people taking part in volunteering abroad was estimated at 10 million, with volunteer tourists spending up to €1.45bn (£1.25bn) on trips in 2019. Demographics and activities vary but volunteer tourism is largely fuelled by young, unqualified and often white volunteers on short-term placements in vulnerable communities.

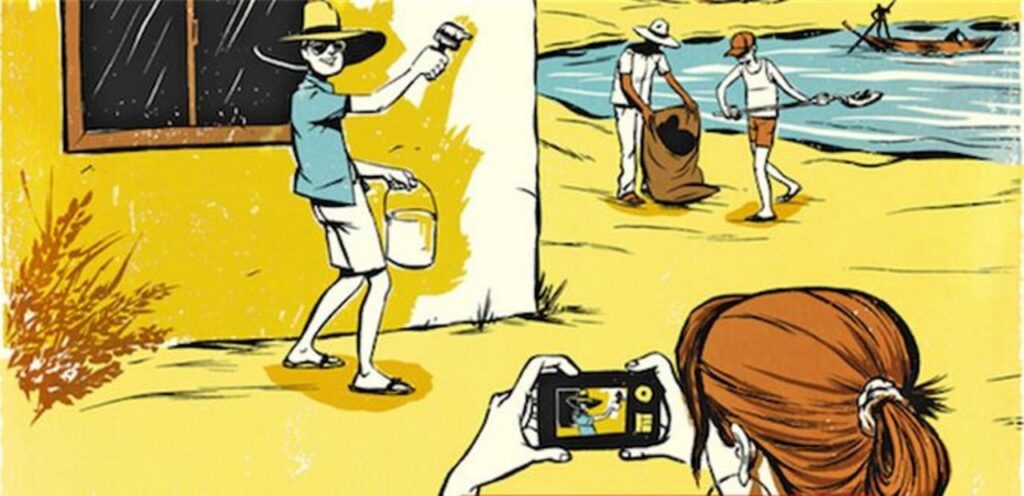

Critics say volunteer tourism turns poverty into a tourist attraction that travelers are eager to see without meaningfully engaging with. Volunteer tourists can inadvertently exacerbate the problems they seek to address, by putting people out of jobs, harming child psychological development or reinforcing belittling stereotypes about poor communities in the developing world.

Biddle dedicates several chapters to exploring how volunteering with children (one of the most popular volunteer activities) can be harmful to their wellbeing and development. For example, volunteering has increased the demand for children to be in orphanages, leading to care facilities offering parents money to recruit children, resulting in family separation. Many organisations do not vet volunteers, exposing children to danger in places with inadequate child protection procedures. The constant turnover of volunteers can cause attachment disorders and affect children’s psychological development.

The book exposes what happens when unqualified volunteers find themselves in situations they are not trained to handle, such as a young medical volunteer who fainted during surgery.

Biddle’s stories suggest the industry is built to meet the needs of volunteers, not communities. But the problem is not simply that volunteers are unqualified, the entire industry seems to be an extension of a colonial mindset and with colonial structures of economic and political power.

Biddle says she does not want to demonise volunteers, but hopes to shed light on the problems. She says the history of volunteer tourism has “too many instances” of westerners deciding what help looks like, and too many stories of communities struggling to have their voices heard.

For those familiar with volunteer tourism or aid work these arguments are not new. But Biddle hopes to make the debate more accessible for beginners.

Incorporating education about colonialism, aid, and privilege can result in more meaningful cross-cultural experiences for volunteers and communities, and Biddle highlights possible solutions – from certification systems for volunteer organisations to better child protection laws. But as a white woman who has made her own mistakes, she says it is not up to her to decide what better volunteering looks like. “The conversation should be led by the communities affected by this,” she says.

Since Biddle’s 2014 blog post, campaigns such as Barbie Savior and No White Saviors have emerged, with calls growing for aid organisations and volunteers to rethink their approach.

But, Biddle says, the volunteer tourism industry continues to operate without systemic change. “There are millions of people every year who think it is OK to buy access to vulnerable children and then disseminate images of them across the internet,” she says. “That is still considered not just OK, but valiant.”

Biddle hopes her experiences will prevent people making the same mistakes. “Don’t do as we did,” she says. “But please, do learn from it.”